Montana State Highway 1 winds for 60 miles between Drummond and just south of Anaconda, tracing the curves of Boulder and Flint Creeks. On a mild day in the middle of November, calves and lambs sit out in pastures under the Big Sky. A light dusting of snow rests on the lower slopes of the Pintlers. A lone fly fisherman stands in the water, casting again and again, and passing barns and sheds are decorated with elk antlers.

A sign announcing Fred Burr Creek, defaced, now reads Fred Burr Crick. Climbing Flint Creek Pass, south of Philipsburg, a moss-choked trickle of water next to the road suddenly gives way, almost magically, to the sweeping view of high peaks off in the distance and glassy-smooth Georgetown Lake to the right.

It is beauty and majesty, writ small and large, the essence of Montana.

If he had his way, Bobby Hauck would get all of his players from country like this. Football, alas, has evolved beyond the point where that’s possible, and so the Montana Grizzlies have a diverse roster this year – a quarterback from Texas, a stud running back from the Twin Cities, wide receivers from California & Canada, and a game-wrecking defensive tackle from Los Angeles.

But there are still places on the field that demand players shaped by this kind of country, positions that self-select for the toughness and discipline and unique, crazy desire that comes from growing up along Highway 1, or on the Hi-Line, or on the flat, lonely plains of Eastern Montana.

All three of the Grizzlies’ starting linebackers – and five of the six total listed on the two-deep – for this week’s apocalyptic Brawl of the Wild against the Montana State Bobcats are from the Treasure State. That’s been a tradition for decades at Montana, and especially in recent years. Marcus Welnel was from Helena, the state capital. Patrick O’Connell was from Kalispell, laid out at the north end of picturesque Flathead Lake. Jace Lewis was from Townsend, a town of less than 2,000 people 35 miles north of Three Forks, which is 30 miles west of Bozeman.

There are other places on the roster where Montana-bred talent shines through, but nowhere where it does so as strongly.

This year, the Griz linebackers feature Levi Janacaro, Tyler Flink and Ryan Tirrell, all from Missoula, and Carson Rostad, from down the Bitterroot in Hamilton. And then there’s Braxton Hill, the man who leads all of them in tackles. Braxton Hill, the pride of Anaconda, Montana.

“It’s special watching him,” said Bob Orrino, Hill’s head football coach for the Anaconda Copperheads in high school. “And everybody I watch a game with, if they’re not from Anaconda or Butte or something, I say, ‘I coached that kid.’ I always brag about it. It makes the people in Anaconda proud, for sure. I see that on social media every weekend. Braxton, he’s our guy, you know, he’s from Anaconda and he makes Anaconda proud.”

***

In 1882, Marcus Daly discovered a rich vein of copper at the Anaconda Mine in the hills near Butte, Montana. Butte, at that time, was already a moderately important gold and silver mining town. Daly’s discovery would make it the Richest Hill on Earth, changing the destiny of that small corner of Southwest Montana forever.

“In 1882 the district produced nine million pounds of copper,” reads a page on the Mining History Association’s website. “In 1883, production leaped over 250%. … By 1896, a five-square-mile section of the earth was producing 210,000,000 pounds of copper a year, over 26% of the world supply, 51% of the United States’, and employing some 8,000 men with a payroll equivalent to $44,000,000 a month in today’s dollars.”

To process the copper ore, Daly built a smelter in Anaconda, 30 miles west of Butte. Every day for years, trains carrying unprocessed ore rolled from the mines in Butte to the smelters in Anaconda, and every day for years, the towns’ fortunes rose together. Butte became fabulously wealthy, the largest city in the United States between Chicago and San Francisco. Anaconda, listed with a population of 700 in the 1880 census, grew to nearly 10,000 in 1900. When a state capital was selected in the 1890s, the final choice came down to Helena…and Anaconda.

Daly and his fellow “Copper Kings” scratched and fought for control of the money pouring out of the ground, but it seemed as though the profits would grow forever. By 1919, the smoke stack at the smelter in Anaconda reached 585 feet above the ground, the largest such structure in the world, taller than the Washington Monument.

“There had been no gradual encroachment of civilization, no creeping in of small farms and little stores,” University of Montana professor K. Ross Toole wrote. “There was no village. First there was nothing, and then all of a sudden there was the world’s largest smelter and around it a raw new city.”

Walking through Anaconda now, echoes of that history can be felt in every brick. It is a place with memories of glory. The smelter closed in 1980, although the smoke stack, lordly as ever, still towers over the town. Anaconda, which reached a high population of over 12,000 in the middle of the 20th century, now sits at just over 9,000. It used to have two high schools, one Class AA and one Class A. Then it had one, and then that one fell from Class AA to Class A and now to Class B. It’s a town of beautiful, colorful single-family homes, and a bar on almost every corner. In the old days, smeltermen coming down from the hill after work would stop at the Owl Bar to draw their paychecks and slug down a beer and a shot, then move on to the Tangerine, and Carmels, and so on down the line. Now, too many of those houses sit vacant, and the wind whistles through the streets at night.

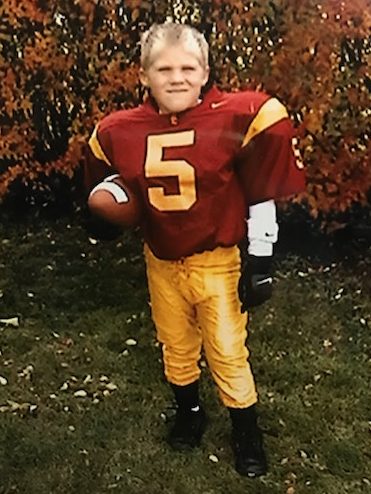

When he was little, Braxton Hill ran through those streets. Ironically for a kid raised in small-town Montana, he idolized the pretty-boy California swagger of the USC Trojans, and dashed around in his red-and-gold, No. 5 Reggie Bush jersey.

“I think he told his mom and dad he wanted a tackling dummy for Christmas or his birthday,” said Pat Gallagher, who was the defensive coordinator at Anaconda when Hill played. “And he used to sit in the backyard and tackle that stupid thing over and over and over. Put the whole pad outfit on and rip the s*** out of the tackling dummy as much as he could. He was a beauty, one of those kids that just loved football.”

He had hometown heroes too. Maybe because it’s soaked in inescapable history, Anaconda is a place that holds its sporting legends close. People like Milan Lazetich, one of three brothers – all three all-state for the Copperheads of Anaconda High – who went on to be a multiple-time NFL All-Pro for the Rams in the 1940s. Or Ed Kalafat, who played with the Minneapolis Lakers the year after George Mikan retired.

Or the greatest of them all – Wayne Estes, who averaged 33.7 points per game for Utah State in 1964-65, second in the nation behind Miami’s Rick Barry. Estes and Barry, in some order, were tabbed to be the first two picks of that year’s NBA Draft. In his final game at Utah State, Estes scored 48 points, giving him 2,001 in his career. On his way home, he and some friends stopped at the scene of a car accident. On his way to help, Estes brushed against a downed power line and was fatally electrocuted.

“It’s definitely blue-collar, small-town Montana that loves its sports and loves its, like, cult heroes, which I think Braxton falls into the category of,” said Jackson Wagner, who grew up in Anaconda and works in Montana’s sports information department. “There’s not a lot of things happening in Anaconda. So even when the teams weren’t as successful, which is true for a long stretch, sports are huge for the people there. And it’s a long lineage of legends too, like Ed Kalafat, and Wayne Estes, and there’s so many more. But there’s a folklore in Anaconda just with the history of the town itself, too.”

Braxton’s father Bill Hill played college football at Eastern Montana College, now MSU-Billings, where he’ll likely forever hold the school’s career rushing record because EMC dropped football in 1978.

Braxton’s older sister, Torry, won back-to-back basketball state titles at Anaconda in 2008 and 2009 before going on to score 1,000 points and make over 200 career 3-pointers for the Lady Griz. For years, she carried the standard of Anaconda on the state-wide stage, as the proud athletic tradition of the town faded away like everything else. Since 1960, just six men from Anaconda have lettered in football for the Griz.

Braxton Hill was always supposed to be next, and he grew up to be the perfect representation of his hometown. In many ways, Anaconda is a tourist town now. People come to fish and hunt and hike through in the wilderness, to ski at Discovery Mountain, and to play golf at the Jack Nicklaus-designed Old Works course, made famous by its black sand bunkers filled with slag left over from the copper smelting process.

But it has never lost its spirit.

It’s a blue-collar town, everybody says – literally the first thing they say when asked to describe Anaconda. It’s still full of hard, tough men and women, who earn their living with their backs and their hands and their sweat, and gather at the corner bar to drink when the day is done. And Braxton was a blue-collar kid. He tagged along to Torry’s basketball games, dribbling his own ball up and down the sideline. In high school, he stayed after practice, working with Ron Estes – Wayne’s brother – practicing his game, drilling moves.

“He would always be the guy, extra reps, extra reps,” Gallagher said. “He was that guy on the football team that would be the first guy there to practice and the last to leave. He had to almost drive the bus when he played for us because he did almost everything already. … He was the quarterback, he played middle linebacker and then he also kicked field goals for us too. And he was good at all three of them because he spent the time doing it.”

Aside from sports, he lived – lived – to hunt and fish. Sitting in the middle of a mountain range with lakes on all sides, Anaconda is an outdoorsman’s paradise. Bill had Braxton hunting and fishing as far back as he can remember. Before school, he would wake up early, ride over to his family friend Gary Brunell’s house, and rig fishing rods. In the fall, he strapped on a backpack and went elk hunting, chasing bulls through the ridges and woods of the Pintlers.

“This is the type of kid, after the game I’ll call him and say, ‘You played one hell of a game,’” Brunell said. “We don’t talk two minutes about his games, and the first words out of his mouth during hunting season are, ‘Did you go hunting?’ If it’s in September, ‘Where’d you go fishing? How many did you catch? What lake were you at?’”

And aside from the sheer joy that he takes from it…well, elk hunting makes you tough, tough in a way that’s hard to describe, tough in a way that most people will never know. Bill and Braxton hunted with Tony and Cory Huot, and Tony’s son Kaden, who’s now a young quarterback on the Griz.

“We always hunted and fished with those guys. But they were always football-based,” Braxton Hill said. “We would hunt, and they’d be like, put a heavy pack on, this is why you run people over when you’re playing football. So even though we’re hunting, they carried toughness and work ethic into hunting, and they related it to football. I mean, hunting is different than football, but I could tie a ton of things to both. Waking up early, working hard. Going when you’re tired. There’s so many things that relate to those two things.”

In the second game of his high school senior year, Hill tore his shoulder. He’d had 31 tackles in the two games. Anaconda, competitive with him, fell off a cliff. It ate at Hill, watching everything slip away, watching his teammates struggle. He returned for the final game of his senior year. Then he played the entire basketball season. He finished his high school career with 1,924 points, breaking Estes’ and Kalafat’s records. Then – and only then – he had surgery.

“When he first started working out, he would work out with me,” Brunell said. “He was just going into high school, and I was in my 40s, and there was just no quit in the kid. We went hiking, freshman year of football, and we were coming out of this lake. I was goddamn tired. I was sucking it. And he goes, ‘Suck it up, c’mon, get going.’ He had a walking stick and he poked me in the back with it. I turn around and go, ‘You poke me with that f****** stick again and I’ll shove it up your ass.’ But he was in such good shape. He wanted to run out.

“Yeah, he is a tough, mentally tough, everything tough kid, but a kid that’s got a heart the size of Texas.”

***

Smelting copper requires the raw ore to be placed, along with a chemical reducing agent, under an intense amount of heat. It doesn’t melt the metal free. Rather, it decomposes the ore around it, resulting in the slag that now fills Old Works Golf Course’s immaculately designed bunkers.

What’s left, after the application of a great deal of energy, is the base metal, gleamingly valuable, the shiny red-gold copper that powered America’s electric revolution, helped the United States navigate a pair of world wars and made Butte and Anaconda into wealthy towns.

It’s modern-day alchemy, arcane transformation, the end result seeming, to outsiders, like magic. A hundred miles northwest of Anaconda, it’s also the process by which Montana Grizzlies linebackers are made.

The base material is not unprocessed ore, but hard, tough Montana kids, raw as Anaconda was in its boomtown days. The crucible is not a smokestack stretching into the Montana sky, but brutal days of winter conditioning and spring ball and fall camp, and the galvanizing motivation of Washington-Grizzly Stadium crowds. The result is not bricks of copper, but All-Americans.

Braxton Hill arrived on Montana’s campus in 2018, still recovering from his shoulder surgery.

“I’m just grateful for Coach Hauck because he saw something in me and gave me a chance,” Hill said. “Coming out of a town like that, you don’t have a lot of coaching, or experience. … I wanted to keep going but I didn’t really know what was out there. I don’t know there’s guys like Levi (Janacaro) who think the same way as me, guys like Gub (Alex Gubner) that you meet there. Then you’re surrounded by a big picture, bigger community, coaches who have been in the NFL, they just know ball. And then things just start clicking and you start getting on the field.”

He grayshirted that year to get fully healthy, then started to go through the process that had molded Dante Olson, Jace Lewis and so many others into stars: Five tackles as a freshman in 2019, mostly on special teams. Twenty-seven tackles as a post-COVID sophomore in 2021, including eight in a road playoff loss at James Madison.

“I feel like the moment that really sticks out to me was James Madison in the playoffs, and he comes in and gets a couple tackles off the bench,” Wagner said. “To hear Anaconda, Montana, on the ESPN broadcast literally brought chills, because it’s just not something that I’ve ever heard in my life. So that was kind of the moment when it was like, whoa, this is real.”

Last year, he broke fully into the lineup alongside Welnel and O’Connell, racking up 66 tackles, three sacks and four pass breakups.

This year, he leads the Griz and is second in the Big Sky Conference with 83 tackles, and has added 2.5 sacks. Ranging from sideline to sideline in a way that belies his solid, squat 6-2, 225-pound frame, Hill had 15 tackles against Ferris State, and 12 more against Northern Arizona. Against Northern Colorado, he intercepted a pass to the flat and returned it 34 yards for a touchdown, getting to celebrate with his fellow “Highway 1 Boy” Jaxon Lee, originally from Philipsburg, who had a pick-six earlier in the game.

“I’ve told people this when he first went and decided to go to the Griz,” Orrino said. “He’s going to do great things. He’s going to be a starting linebacker. I’ve told people that. He’s an animal. When he first chose to go with the Griz, people were saying well, he’s not fast enough at that level. He’s not this. He’s not that. I just said sit back and watch, because I know what’s going to happen, because he’s such a hard worker.”

He’s been a crucial part of a Montana defense that replaced All-Americans in O’Connell, Robby Hauck and Justin Ford and still improved, allowing just 15.2 points and 311 yards per game entering Saturday’s showdown against rival Montana State.

In the fall, when he’s not leading the Griz defense, Braxton Hill steals away, back down Highway 1. He goes hunting. He goes fishing. He takes his teammates – Janacaro and Flink and the rest of the Montana boys, but also guys like Riley Wilson, who was raised in Texas and transferred over from Hawaii. And even if Braxton Hill isn’t thinking it, when he’s walking through the mountains, it’s a reminder: This is where Griz linebackers are from. This is what made Braxton Hill what he is.

“I’ve always just wanted to do well, for everyone,” Hill said. “People were just so supportive and appreciative and they loved watching, and they encouraged me so much that it just turned into motivation and just made me want to compete that much harder. You know, playing for the brotherhood in high school, and then playing for the town. And then when you get to college, it’s elevated.

“We run in that empty stadium all summer long. You don’t think about this when you’re younger, but when you’re older, and you’re running in that stadium, and you want to let up a little bit, you don’t. You look around that stadium, you know it’s gonna be packed. That’s what drives me when I’m out there running. Knowing that stadium’s gonna be packed and that they’re gonna bring it and that Wa-Griz is gonna be rockin’, I’m gonna work as hard as I possibly can when no one’s watching for those moments.”

Photos by Brooks Nuanez and Blake Hempstead – Skyline Sports. All Rights Reserved.