In 1989, Bob Stitt was a graduate assistant at Northern Colorado. That fall, the town of Greeley played host to the Denver Broncos’ training camp. John Elway was there. Bobby Humphrey was there. Steve Atwater was there. It was about six months before the Broncos would play in the Super Bowl against Joe Montana, Jerry Rice and the San Francisco 49ers.

In attendance alongside Stitt was the coaching staff of the Mississippi Valley State football program. What they were there to learn is uncertain, but it probably had something to do with returning the Delta Devils to success they had when Rice was scoring touchdowns at a ridiculous pace for the 1-AA team a few years earlier.

When Rice was there in the early 1980s, Mississippi State started to experiment with a new style of offense that unpacked the box, trading running backs and tight ends for wide receivers. Instead of running the ball, the Delta Devils started to throw it around the field and they started to score at an alarming rate. With Rice and quarterback Willie ‘Satellite’ Totten as the focal point of the Satellite Express, the Delta Devils averaged more than 61 points per game in 1984. In the first game of that season, MVSU beat Kentucky State 86-0. The next week it was a 77-15 win over Washburn.

“Our defense didn’t know how to stop it practice and I think coach’s philosophy was if they can’t stop it in practice, how can someone else stop it if they’ve never seen it before?” said Totten, now a quarterbacks coach at Alabama A&M, earlier this week. “Or if they only had two to three days to practice for it, try to prepare for it. When we started running it, it was exciting.”

The Delta Devils began doing strange things on offense. Not only were they spread across the field, concerned far more with throwing the ball than running it, they were positioning receivers in very odd formations. Sometimes they stranded Rice to one side and put all the other receivers on the other. Other times they would put their receivers on one side of the field — all five of them — stacked in a straight line to attack a confused defense.

So when Stitt was there in Greeley with the staff from Mississippi Valley State in the fall of 1989, a friend of his wandered up the coaches with one question in mind.

“One of my friends asked them if they were still doing the stack and he’s like, ‘We don’t have Jerry Rice anymore,’ Stitt laughed. “I remember that like it was yesterday.”

Twenty-seven years later Stitt is preparing 10th-ranked Montana Grizzlies to play a Mississippi Valley State team that has fallen on hard times. The Delta Devils went 8-3 in 1985, Totten’s last year on campus and the year after Rice graduated, but have experienced just a handful of winning seasons since. They come to Missoula on Saturday 0-5 with just three wins in the last two seasons. And they’ll be tasked to stop an offense that has considerable differences from that one that once made the Devils a fan favorite of college football fans around the South, but one that owes its roots to minds like Archie Cooley, the coach who made the Satellite Express possible.

When Willie Totten was in high school, he was a quarterback of a team that ran the Notre Dame Box, a variation of the single wing offense that kept the ball on the ground and robbed Totten of showcasing his arm for college scouts. He arrived in Itta Bena, Mississippi as a punter/quarterback staring down the barrel of a competition with eight other signal callers.

The summer he stepped on campus in 1981 coincided with the arrival of Jerry Rice, the son of a bricklayer from Starkville, Mississippi who started as a true freshman that fall, became a bigger part of the offense as a sophomore and then started breaking 1-AA records as a junior.

Once Cooley, a former defensive coach at Tennessee State, decided to ditch the veer the Devils were running in favor of an offense a small group of teams around the nation were starting to experiment with, MVSU started to become indefensible.

“I would save the best five plays that the opponent ran against Tennessee State’s defense, when Coach (Joe) Gilliam was the coordinator at the time,” Cooley told Fox Sports in a 2014 interview. “I could hardly wait during practice to do that. It was my whole highlight of practice. So my offensive mind grew tremendously simply because I took a lot of pride in doing what I was doing.”

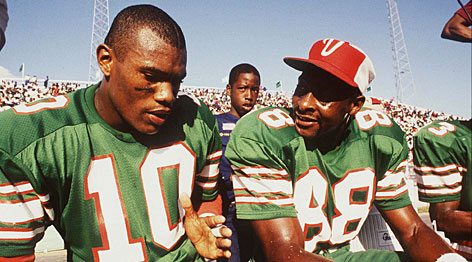

Jerry Rice, wildly considered the greatest wide receiver of all time, cut his teeth at Mississippi Valley State/ courtesy of MVSU athletics

But even then, as Rice caught 102 passes from Totten, the offense wasn’t complete. Then one day in 1984, one of the MVSU coaches asked Cooley why they were huddling. What was the point when they were just going to run the same play regardless of the huddle? At that moment, the full power of the offense was unleashed.

The MVSU defense, unaware of the scheme it’s offense was going to be running, couldn’t figure out how to stop it. Totten and Rice and the rest of the offense used to look forward to practice just to see how many touchdowns they could throw in each session. Totten recalls that sometimes it was eight, sometimes 12, sometimes 15. But regardless of the day it was go, go, go for the Delta Devils offense.

“I’ll never forget the week that we started running the no-huddle,” Totten said. “I actually had total body cramps. I cramped up. Half of the guys — receivers — was cramping up because it was run, run, run, fast paced, fast paced, run, run, run, fast paced. It was something that we had to get used to too. We had to get used to the offense as well.”

Eventually they did, but opposing defenses couldn’t. Mississippi Valley put up 163 points in the first two weeks of the season.

“It was kind of like, ‘Wow, OK, this is what this offense is going to be about,’” Rice told Fox. “But we still just felt like we needed to keep tuning that offense, that system and that speed of play, and we felt we’d be able to do great things on the football field.”

A week later, Rice caught 15 passes for 285 yards Mississippi Valley scored 49 points to beat rival Jackson State for the first in 27 years. The points continued to pile up and people started to take notice. They started to give nicknames to players. Rice was given the moniker ‘The World’ because he was all over the field, and Totten ‘Satellite’. Even the offensive line was given a nickname — ‘Tons of Fun’.

“Everybody was having fun in the offense,” Totten remembers. “When you get those nicknames and you’ve — I think it was a world beater for commentators who were calling the games on TV. We played a lot of games on TV. At the time it was BET. When you’ve got the announcers saying, ‘There goes Jerry ‘World’ Rice.’ It had a ring to it. That made it exciting. People wanted to come see who in the heck is this Jerry ‘World’ Rice? Who is this Willie ‘Satellite’ Totten? Who is this Truck Byron? Those kind of names kind of caught on and it really made it exciting.”

Mississippi Valley continued to win games, entering the 1-AA playoffs 9-1 after losing by just four points to Alcorn State in front of more than 63,000 fans at Mississippi Veterans Memorial Stadium in Jackson. But that was as far as they went, dropping a lopsided first-round playoff game to Louisiana Tech. That season, Totten threw for 5,043 yards and 58 touchdowns. Rice finished with a then NCAA record of 112 receptions and 28 touchdowns to go with 1,845 yards. He caught 24 passes against Southern, a single-game NCAA record.

Rice finished his career as the Division I all-time leader in catches (310), yards (4,856) and touchdowns (50). He went on to a Hall of Fame NFL career that included more than 1,500 catches, 22,000 yards, 200 touchdowns and three Super Bowl rings.

Though the Satellite Express differs from Stitt’s offense in a number of ways, primarily that MVSU was throwing the ball with little regard for the run game, while Stitt’s offense — more influenced by the West Coast system created by Bill Walsh’s 49ers teams that made Rice an NFL star— utilizes the run to set up the pass, MVSU’s trail blazing helped change the landscape of college football.

“Every time when people talk about that people remember what we did 30 years ago,” Totten said. “We ran that offense. It was potent then and is now. Teams are running it now and they’re being very, very effective. If you run it and you have the personnel to run, it’s a very difficult offense to stop. Just lookin’ at the offense now and you really got a quarterback who can throw and you got receivers who catch it now. They’re doing a little more than running the screens with it now. We didn’t run screens. We ran pretty much just a quick pass. People have added the screen to it. They added the RPOs to it and it really made the offense really, really hard to stop.”